This blog post recounts a mini research study on reasoning LLMs that I embarked on in April 2025 as part of CMU's 76-101 Undergraduate First Year Writing course (main link, mirror). I was fortunate to enroll in the GenAI section of the course, which means that the texts we were learning about in class were related to GenAI (the singularity, benefits/downsides/opportunities/fears in this new era etc.) The course trains students to do research, and so the final exam is to write a mini paper. I wanted exposure to reasoning LLMs, so I obtained special permission to do a technical project.

The full paper is detailed below. If you do go through it, thank you very much for your time. I am always reachable via email (see the left sidebar) to learn from any criticism.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Synthesis

- 2.1. Definition of Key Terms

- 2.1.1. Reasoning

- 2.1.2. Structural Causal Model (SCM)

- 2.1.3. Outcome & Process Supervision

- 2.2. Overview of Current Research and Gap

- 3. Methodology: Case Study

- 3.1. Outcome-Supervised Model

- 3.2. Process-Supervised Model

- 3.3. Evaluation to uncover faulty causal structures

- 3.4. Repetition of Evaluation under 16-shot CoT setting

- 4. Results

- 5. Discussion

- 5.1. Outcome Supervision outperforms Process Supervision in this specific case

- 5.1.1. Possible Explanation of Main Finding

- 5.1.2. Main Finding's Relation to Prior Work

- 5.2. 16-shot CoT prompt affects task accuracy but does not fix underlying SCMs

- 5.3. Limitations and Future Work

- 6. Conclusion

- Appendix A

Abstract

There is growing interest in training Large Language Models (LLMs) to specialize in reasoning tasks across mathematics, logic and coding. However, the types of reasoning errors associated with various supervision strategies remain relatively understudied under rigorous control of confounding factors. In this study, a publicly available Qwen-2.5-7B model trained with Outcome Supervision via Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) was compared to a Process-Supervised counterpart trained via Supervised Finetuning on gold chains-of-thought (CoT), with token exposure and optimizer update frequency held constant. Both models were evaluated using a framework designed to detect spurious correlations between the prompt, CoT, and final answer, revealing instances where reasoning bypassed the CoT. Results showed that both models were susceptible to CoT bypass, but the Outcome-Supervised model exhibited slightly lower incidence. Moreover, its task accuracy significantly outperformed the Process-Supervised model under a 0-shot CoT setting. Interestingly, a 16-shot CoT prompt hurt the Outcome-Supervised model's task accuracy and improved the Process-supervised model's performance, yet neither model's underlying Structural Causal Models shifted, suggesting that prompt-level interventions are insufficient to alter core reasoning patterns. These findings indicate that RL-based Outcome Supervision may yield more robust reasoning under the conditions studied, as each gradient update potentially provides a richer learning signal. However, they also highlight the limitations of the methods employed to align training effort, underscoring the need for even more rigorous evaluation strategies in future work.

1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have significantly impacted several industries due to their remarkable instruction following abilities. The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 [1] popularized LLMs and ignited fervent global interest in enhancing their capabilities to address complex reasoning tasks in mathematics, logic, and software development. As the LLM field developed, model performance on reasoning benchmarks improved substantially [2], sparking debate on whether such systems genuinely reason or merely excel at sophisticated pattern-matching* [3]. Initial efforts to encourage human-like "reasoning" involved experimenting with variants of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, where LLMs are instructed to explicitly articulate intermediate reasoning steps [4]. The field has since transitioned to techniques such as Outcome Supervision and Process Supervision [5], which train LLMs to autonomously generate CoTs and "ruminate" on challenging inputs for longer. LLMs fine-tuned using such techniques are now colloquially known as "large reasoning models (LRMs)".

*: By "pattern matching", this study means that instead of systematically applying logical rules, LLMs generate text by predicting the statistically most probable continuation based on patterns learned from training data [6].

LRMs significantly outperform their non-reasoning predecessors on complex mathematics, logic and coding tasks, thus there is widespread interest in deploying them to generate practical value. Yet, LRMs continue to make surprisingly basic common-sense errors [7], [8], raising doubts about their reliability. This uncertainty has heightened the urgency to investigate whether they genuinely reason and determine how they can be made more robust. However, only a minority of papers have deeply analyzed the reasoning capabilities of modern LRMs beyond task performance [9]. Within this subset, even fewer studies have empirically characterized the various types of reasoning errors that are associated with different LRM training strategies.

To address this gap, this study investigated whether the choice of training strategy affects an LRM's tendency to "bypass" its CoT and rely directly on the input prompt to derive its final answer. Two LRMs, one trained with Outcome Supervision via Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards, and the other with Process Supervision via Supervised Finetuning, were prepared such that both models encountered the same training data and received optimizer updates at similar frequencies. Their reasoning behaviors were then compared using an evaluation framework [10] that infers the underlying Structural Causal Model (SCM) by detecting faulty causal links between the prompt, CoT, and final answer. Results indicated that both models were prone to "CoT bypass" errors as they frequently exhibited spurious correlations between their prompts and final answers. However, the Outcome-supervised model demonstrated greater robustness overall. These findings offer insights into the relative strengths of the two supervision strategies and the limitations of aligning training effort by controlling just the data exposure and optimizer update frequency. This informs both model development and safety considerations for real-world deployment.

2. Synthesis

To study the failure modes associated with various LRM training techniques, it is necessary to clarify the reasoning errors being considered and the training techniques being compared, before examining the AI field's present understanding of whether LRMs truly reason.

2.1. Definition of Key Terms

2.1.1. Reasoning

This study adopts Proudfoot & Lacey's definition of reasoning as the application of logic to draw valid conclusions from new or existing information in the pursuit of truth [11].

2.1.2. Structural Causal Model (SCM)

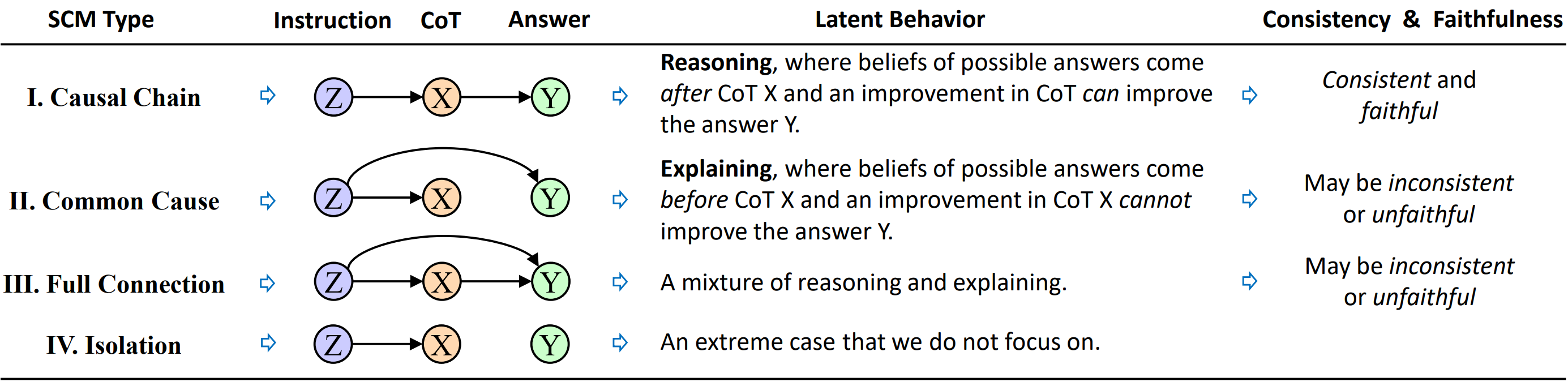

A Structural Causal Model (SCM) is a mathematical model that represents causal relationships within a system [12]. This study focuses on the four SCMs proposed by Bao et al. to model reasoning behaviors in LLMs [10], as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Screenshot of a table from Bao et al. (2025)'s paper, showing the four SCMs proposed to model correct reasoning (I) and faulty reasoning (II, III, IV). The prompt, CoT and final answer are denoted with , and respectively.

Figure 1. Screenshot of a table from Bao et al. (2025)'s paper, showing the four SCMs proposed to model correct reasoning (I) and faulty reasoning (II, III, IV). The prompt, CoT and final answer are denoted with , and respectively.

In SCMs II (Common Cause) and III (Full Connection), there is an arc from to , indicating that the LLM exhibits spurious correlations between the prompt and final answer that are independent of the CoT. SCM II represents a complete bypass of the CoT, with the final answer determined solely by the prompt, whereas SCM III reflects influence from both the CoT and prompt. These two classes of reasoning errors are the focus of this study. Accordingly, this study examined which SCMs were implied by each of the two LRMs under comparison. This enabled an analysis of whether the LRM training strategy affected the tendency to bypass the CoT, and if so, the severity of this bypass.

2.1.3. Outcome & Process Supervision

This study compared Outcome Supervision and Process Supervision, two prominent classes of techniques for training LRMs. Both approaches extend the idea of CoT prompting [4], which guides LLMs to articulate intermediate reasoning steps. Unlike basic CoT prompting, Outcome and Process Supervision incentivize models to autonomously generate CoTs and allocate greater cognitive effort to harder inputs. According to Uesato et al. [5], each supervision strategy can be further subdivided as follows:

- Outcome Supervision via Reinforcement Learning (RL) with verifiable rewards (RLVR): The model receives a scalar reward based solely on the correctness of its final answer, as determined by a simple rule-based verifier. No reward is issued if the answer is incorrect.

- Outcome Supervision via RL with LLMs as judges: A separate LLM, termed the Outcome Reward Model (ORM), evaluates the final answer and assigns a reward, replacing the rule-based verifier.

- Process Supervision via Supervised Finetuning (SFT): The model is trained directly on human-written gold CoTs using standard supervised learning, without any RL.

- Process Supervision via RL using LLMs as judges: A separate LLM, termed the Process Reward Model (PRM), assigns stepwise rewards based on the correctness of the reasoning up to each step. Due to resource constraints, this study compared an LRM trained with Outcome Supervision via RLVR to one trained with Process Supervision via SFT.

2.2. Overview of Current Research and Gap

Since LRMs are a relatively recent development within the broader class of LLMs, it is instructive to first adopt a wider perspective by reviewing the literature on whether LLMs can reason. Most studies have approached this question by evaluating model performance on reasoning benchmarks [9]. Over the years, benchmark scores have surged, driven by techniques like CoT prompting [4] and self-consistency [13] in the pre-LRM era, and more recently by LRMs like DeepSeek-R1 [14]. However, there has been mounting concern that benchmark performance does not clearly indicate whether models are improving at genuine reasoning or pattern matching, as LLMs continued to struggle with basic logic puzzles [7], [8]. Even modern LRMs, while stronger overall, often fail when faced with minor variations in problem structure [15]. As a result, the field has increasingly shifted towards evaluating reasoning beyond task performance by directly inspecting CoTs for reasoning errors.

However, within the minority of studies that pursue direct CoT evaluation, most continue to focus on older, non-reasoning LLMs rather than modern LRMs. For example, Bertolazzi, Gatt & Bernandi tested LLaMA-3 and Pythia on syllogisms, using cognitive psychology frameworks to show that LLMs are influenced by reasoning heuristics such as content effects [16]. Bao et al. proposed an evaluation framework that detects spurious causal links between the prompt, CoT, and final answer, enabling classification of the underlying SCM (see Section 2.1.2) and revealing instances where a model bypasses its CoT [10].

Amongst the subset of papers in this minority that do focus on modern LRMs, there is an emerging consensus that Process Supervision tends to yield more reliable reasoning than Outcome Supervision. Uesato et al. manually inspected the CoTs of LRMs trained with variants of Outcome Supervision and Process Supervision, and found that while both approaches achieved high final-answer accuracy, Process-supervised models exhibited significantly lower trace error rates [5]. Lightman et al. extended this finding by training PRMs and ORMs to automatically rank CoTs and showed that PRM-guided supervision led to substantially higher reasoning quality [17].

However, despite these advances, prior work has not rigorously matched training effort across supervision strategies. In both Uesato et al. [5] and Lightman et al. [17], models were trained without very strict alignment of data exposure, optimizer updates, or resource budgets. Lightman et al. did conduct a small experiment that ensured the supervision strategy was the sole independent variable, ceteris paribus; however, this experiment was limited to training reward models rather than the LLMs themselves. Thus, while the field recognizes the superiority of Process Supervision, it remains unclear how reasoning quality would differ if two LRMs were trained under each strategy while controlling for as many variables as possible.

Moreover, existing studies have primarily compared the aggregate reasoning error rate, without systematically characterizing the specific families of reasoning errors associated with each training strategy. As a result, the question of whether different supervision methods predispose models to distinct types of reasoning failures is still unresolved.

These two gaps motivated the present study, which prepared two LRMs trained with different supervision strategies but aligned training efforts, then compared them using Bao et al. (2025)'s framework to assess if either model was more prone to "CoT bypass" errors corresponding to SCM types II and III. This approach contributes to the field by providing an empirical analysis of how susceptibility to a specific family of reasoning errors varies under different supervision strategies when training variables are held as constant as possible.

3. Methodology: Case Study

The AI field increasingly recognizes that Process Supervision tends to yield more reliable reasoning than Outcome Supervision in LRMs. However, there has been little detailed characterization of the failure modes associated with these training strategies under conditions where training hyperparameters are closely aligned. Therefore, this work conducted a case study of the "CoT bypass" error in LRMs. Two LRMs, trained with different strategies but matched training efforts, were compared with Bao et al. (2025)'s framework to infer the underlying SCMs and differentiate if either model exhibited this error more often. The independent variable was the LRM supervision strategy, while the dependent variable was the implied SCM structure.

3.1. Outcome-Supervised Model

Qwen-2.5-7B-SimpleRL-Zoo from Zeng et al. was chosen as the Outcome-supervised model [18]. It was trained using outcome supervision via RL with verifiable rewards on ~8000 of the harder questions in the MATH dataset [19]. For brevity, this model will be referred to as Zeng-OS to reflect its creator and outcome-supervised training.

3.2. Process-Supervised Model

As there was no process-supervised equivalent for Zeng-OS, this work introduced Cheong-PS to provide a comparable baseline. Cheong-PS was obtained by supervised fine-tuning of the Qwen-2.5-7B base model on the same set of math questions used to train Zeng-OS. Hyperparameters were matched as closely as feasible; minor deviations were necessary due to differences in training methodology. The two most important ways in which Cheong-PS's training matches Zeng-OS are outlined below. Further details are in Appendix A.

- Dataset: Zeng-OS was trained on 8,522 challenging questions (Levels 3-5) from the MATH dataset, using only final answers as outcome supervision. With a rollout size of 8 and 90 total rollouts, each question was seen approximately 86 times (Appendix A). To match this token exposure, Cheong-PS was trained on the same 8,522 questions. For each question, 86 gold CoTs were randomly sampled from the math-train-qwen-rs-n256 dataset by Yeo et al. [20]. If fewer than 86 were available, the original MATH gold CoT was duplicated to reach the target count. Cheong-PS was then trained for a single epoch over this dataset.

- Optimizer Step Frequency: Zeng-OS was trained with a PPO micro batch size of 256 and received 1 gradient update after every 256 prompts. To approximate this behavior, the batch size, gradient accumulation and sample packing settings were adjusted such that Cheong-PS also received 1 gradient update every ~268 prompts (Appendix A).

3.3. Evaluation to uncover faulty causal structures

Both models were then evaluated using Bao et al. (2025)'s methodology [10]. Completions were generated for seven tasks: 4 mathematics tasks (6-digit addition, 9-digit addition, 3-digit multiplication, and GSM8K [21]) and 3 logical reasoning tasks (ProofWriter [22], FOLIO [23], LogiQA [24]).

For each model-task pair, two hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1 (CoT Answer): The chain-of-thought causes the final answer.

- Golden CoT Substitution: The prompt was held fixed. The CoT generated by the model was replaced with a gold, human-written one. The prompt and gold CoT were then concatenated and sent to the model. Accuracy was expected to approach 100%.

- Corrupt CoT Substitution: The prompt was held fixed. For the 4 mathematics tasks, the CoT was corrupted by randomizing numerical values in the final two-thirds. For the 3 logical reasoning tasks, the CoT was corrupted by using gpt-4o-mini-2024-07-18 to invert logical statements within a randomly selected section of the final two-thirds. The prompt and malformed CoT was then concatenated and sent to the model. The prompt and malformed CoT were then concatenated and sent to the model. Accuracy was expected to collapse to 0%.

Hypothesis 2 (Prompt Answer, independent of CoT): The prompt alone determines the answer, regardless of the CoT.

- Random Role in Prompt: The CoT was held fixed. The prompt was modified to instruct the model to solve the question while acting in a randomly assigned role: "math teacher," "chef," "detective," or "judge."

- Bias in Prompt: The CoT was held fixed. A distractor, "I think the answer is

[Wrong Option]," was appended to the end of the prompt.

In both cases, the modified prompt was concatenated with the CoT and sent to the model. If the model were performing genuine reasoning, such perturbations would not affect accuracy. Each intervention under Hypothesis 2 was applied using both the model-generated CoT and gold CoT. Based on the effects of these interventions, model behavior on each task was categorized into one of the four SCMs depicted in Section 2.1.2.

3.4. Repetition of Evaluation under 16-shot CoT setting

The default setting of Bao et al. (2025)'s framework employed a 0-shot CoT prompt. This instructed the model to output its result in a specified format while articulating intermediate reasoning steps. However, no human-written examples were provided to guide the model. Thus, the full evaluation was also repeated with a 16-shot CoT prompt, which included 16 human-written examples to assist the model on how each task should be conducted.

4. Results

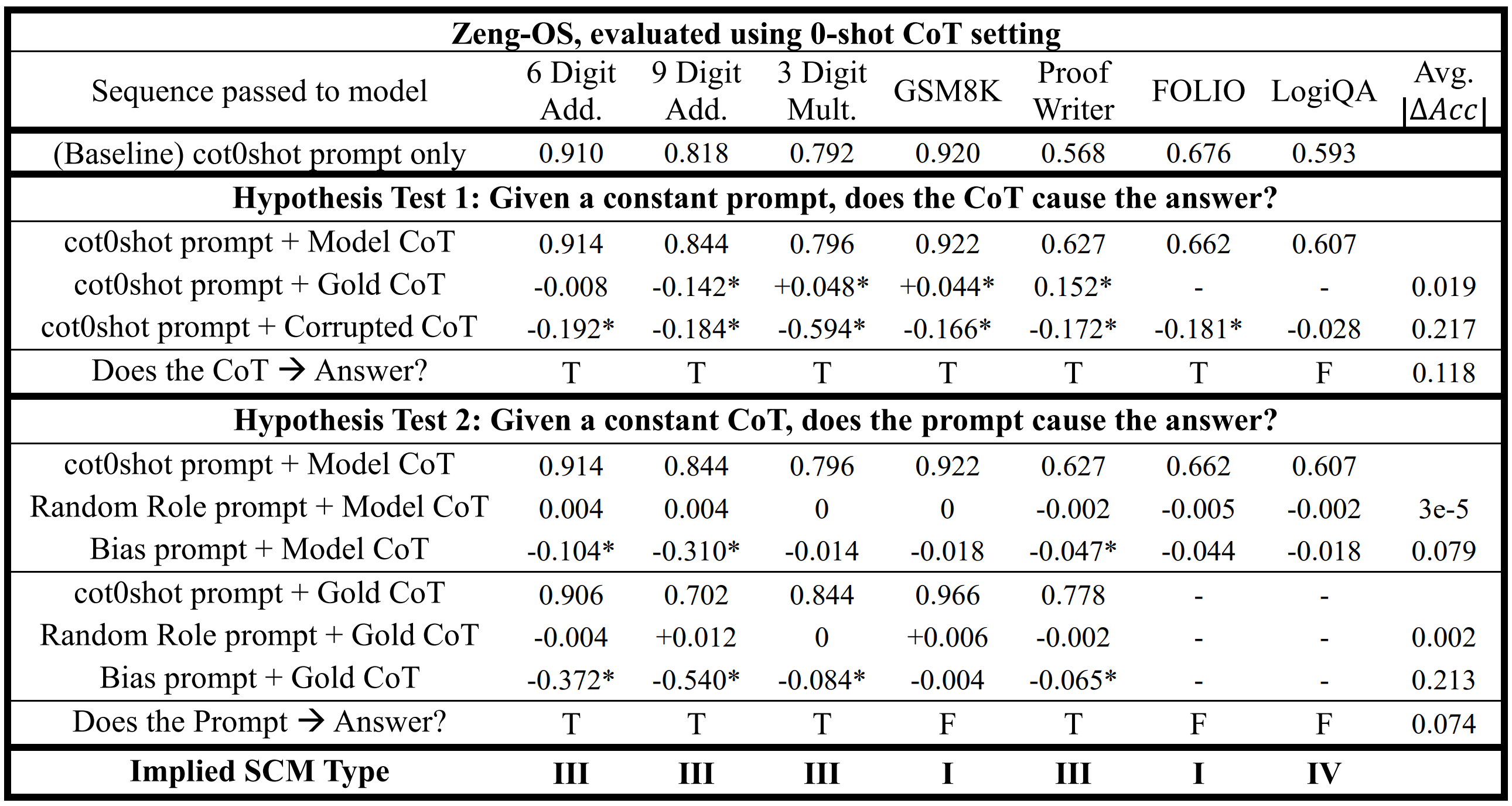

Table 1. Identification of SCMs in Zeng-OS, using the 0-shot CoT setting. Reported numbers are task accuracies, represented as a percentage of correct answers ranging from 0 to 1. "Model CoT" is the model-generated CoT from the baseline. "Avg. " refers to the average absolute change in task accuracy introduced by a particular intervention. The symbol "" denotes a significant difference in task accuracy with p-value < 0.01 as indicated by McNemar's test. If a column has at least one "", the corresponding question for the hypothesis test is answered with "T" for True.

Table 1. Identification of SCMs in Zeng-OS, using the 0-shot CoT setting. Reported numbers are task accuracies, represented as a percentage of correct answers ranging from 0 to 1. "Model CoT" is the model-generated CoT from the baseline. "Avg. " refers to the average absolute change in task accuracy introduced by a particular intervention. The symbol "" denotes a significant difference in task accuracy with p-value < 0.01 as indicated by McNemar's test. If a column has at least one "", the corresponding question for the hypothesis test is answered with "T" for True.

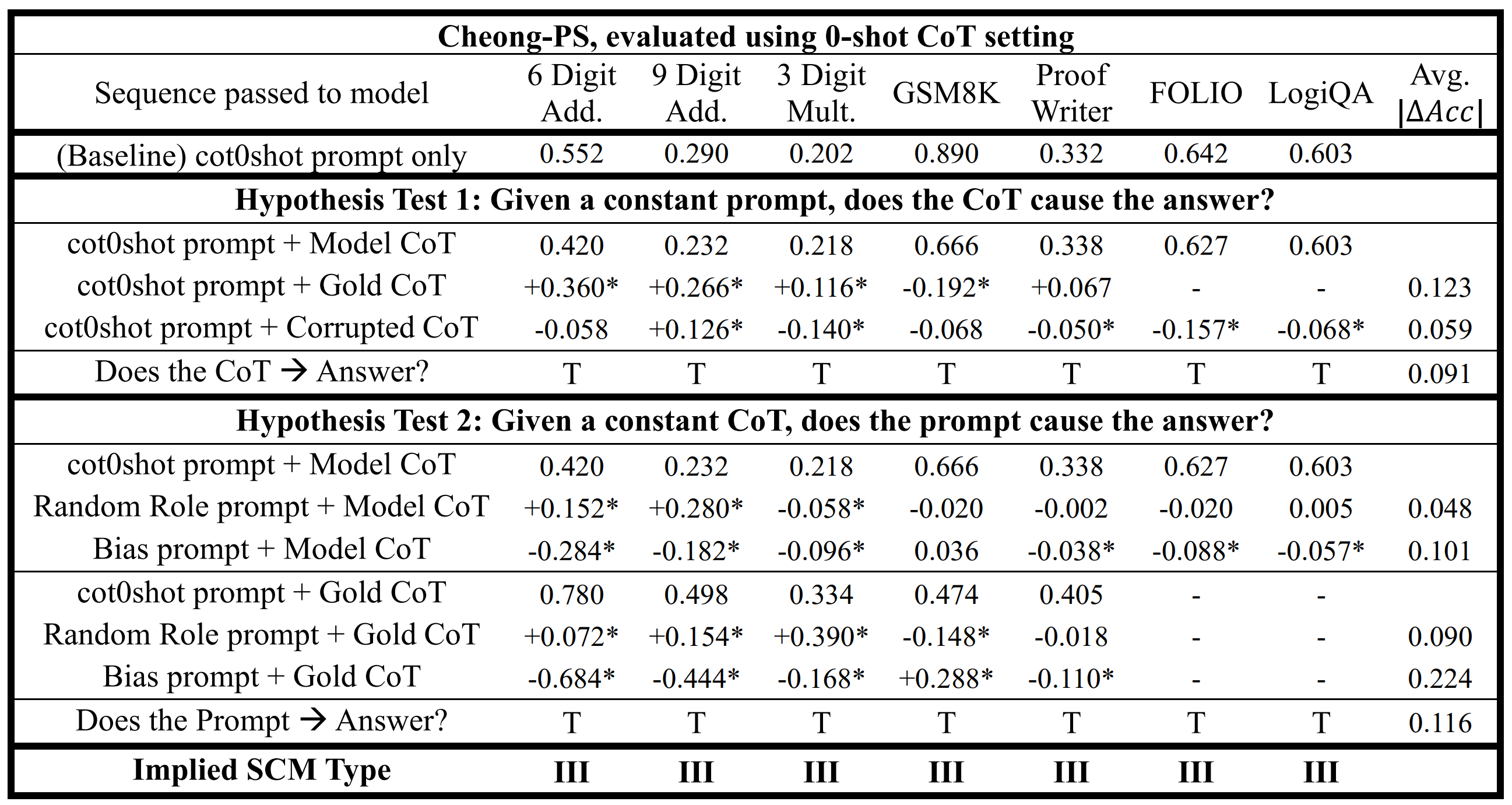

Table 2. Identification of SCMs in Cheong-PS, using the 0-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "", and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

Table 2. Identification of SCMs in Cheong-PS, using the 0-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "", and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

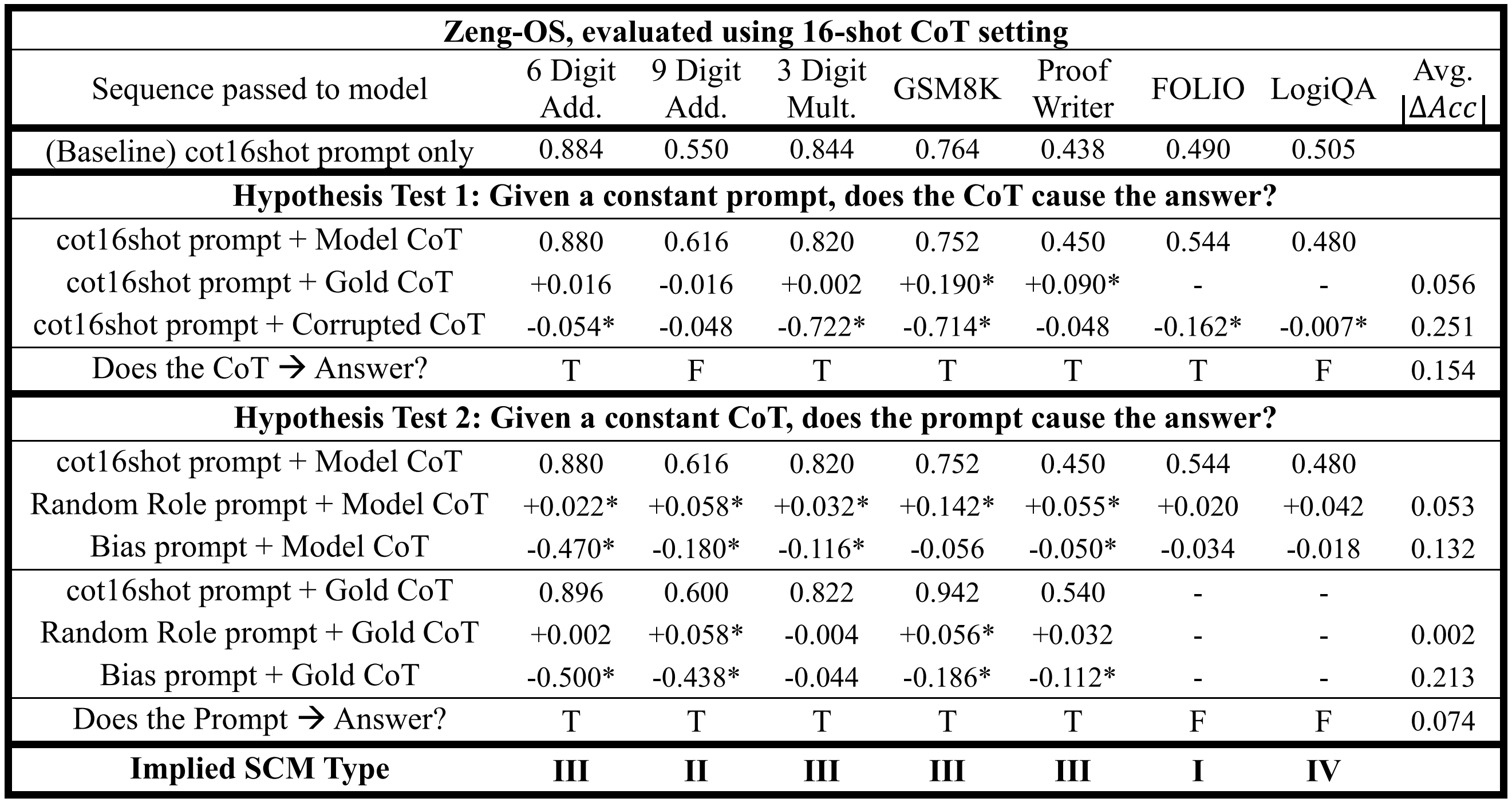

*Table 3. Identification of SCMs in Zeng-OS, using the 16-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "",

and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

*Table 3. Identification of SCMs in Zeng-OS, using the 16-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "",

and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

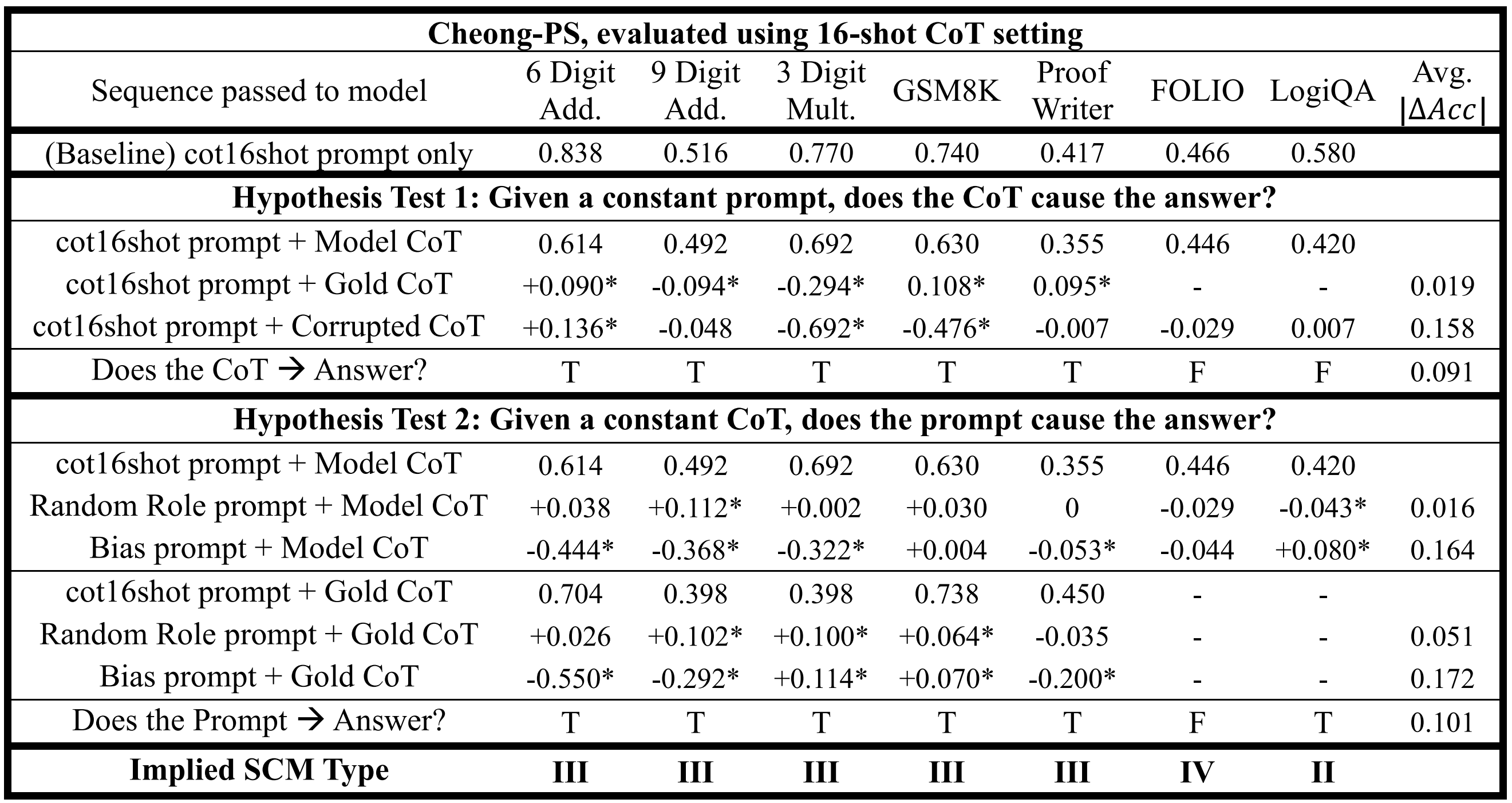

Table 4. Identification of SCMs in Cheong-PS, using the 16-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "", and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

Table 4. Identification of SCMs in Cheong-PS, using the 16-shot CoT setting. For an explanation of "Model CoT", the symbol "", and "Avg. ", please refer to Table 1's caption.

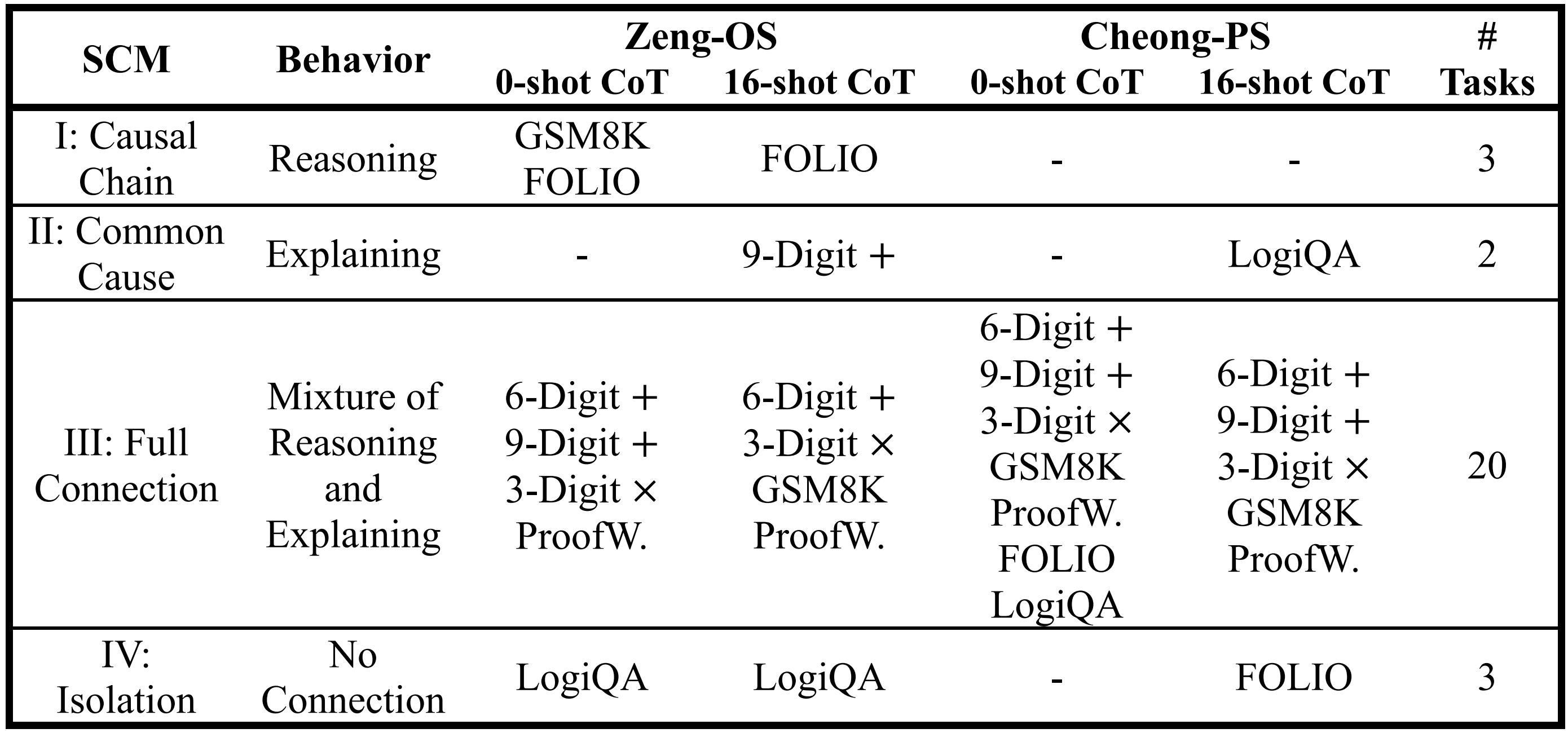

Table 5. Distribution of SCM types in Zeng-OS and Cheong-PS across both 0-shot and 16-shot CoT settings. The results are aggregated from Tables 1-4.

Table 5. Distribution of SCM types in Zeng-OS and Cheong-PS across both 0-shot and 16-shot CoT settings. The results are aggregated from Tables 1-4.

With reference to Table 5, across both the 0-shot and 16-shot settings, Zeng-OS and Cheong-OS both frequently exhibited SCM III behaviors, indicating that both models were susceptible to "partial CoT bypass" errors (a full bypass would correspond to dominance of SCM II). Cheong-OS did not display SCM I patterns on any task, indicating that it failed to perform correct reasoning across all benchmarks. In contrast, Zeng-OS reliably achieved SCM I structures on FOLIO, suggesting genuine reasoning ability, but it also consistently produced SCM IV structures on LogiQA, indicating that its answers for LogiQA were independent of both the prompt and CoT.

In addition to the overall SCM distributions, several specific deviations from expected logical behavior were observed. In some cases, providing the gold CoT led to a decline in task accuracy, despite the gold CoT placing the model very close to the correct answer. This counterintuitive result was observed for Zeng-OS on 9-digit addition (Table 1) and for Cheong-PS on GSM8K (Table 2). In another instance, perturbing the prompt by inserting a random role did not significantly impact Zeng-OS's performance (Table 1), but unexpectedly boosted Cheong-PS' accuracy (Table 2). Finally, when the prompt was biased with the distractor, both models exhibited noticeable performance degradation despite the distractor being logically irrelevant. These observations collectively reinforce that neither model was routinely performing genuine reasoning, consistent with their predominant classification as SCM III.

When comparing baseline performance under the 0-shot CoT setting (Tables 1 and 2), Zeng-OS achieved higher accuracy than Cheong-PS across all tasks except LogiQA, where it trailed by ~0.01 accuracy points. In several tasks, including 6-digit addition, 9-digit addition, and 3-digit multiplication, Zeng-OS outperformed Cheong-PS by large margins, achieving 0.80-0.90 accuracy compared to 0.20-0.40 for Cheong-PS. Qualitative examination of model outputs revealed that on these tasks, Cheong-PS frequently failed to terminate its responses properly: it either failed to emit the end-of-sequence (EOS) token, or produced the correct answer early in the sequence, but continued generating incoherent or repetitive text until it was cut off by the maximum response length. In contrast, Zeng-OS maintained output consistency across tasks

Finally, when considering results under the 16-shot CoT setting, it is observed that the 16-shot prompt significantly influences task accuracies, but the implied causal structures remain largely invariant. Comparing Tables 1 and 3, the baseline performance of Zeng-OS decreases after the 16-shot prompt is introduced, even though providing additional examples would typically be expected to improve model performance. In contrast, Cheong-PS exhibited the opposite trend: while it struggled under the 0-shot CoT setting, its task accuracy improved when provided with more examples (Table 2). Nevertheless, despite these shifts in task accuracy, the classification of the underlying SCMs remained largely unchanged.

5. Discussion

5.1. Outcome Supervision outperforms Process Supervision in this specific case

The results indicate that the choice of supervision strategy does affect an LRM's tendency to exhibit the "CoT bypass" error. Since Zeng-OS exhibited more SCM I structures and significantly outperformed Cheong-PS under the 0-shot setting, the Outcome-Supervised model had a lower incidence of "CoT bypass" and outperformed the Process-Supervised model, which might be unexpected given the existing literature. The following subsections propose possible explanations for these findings and argue that this result does not contradict prior work. Rather, it provides an additional perspective that enriches the understanding of the outcomes one can expect when comparing LRMs trained with fundamentally different supervision strategies under controlled conditions.

5.1.1. Possible Explanation of Main Finding

Although Zeng-OS and Cheong-PS saw the same training data and received optimizer updates at very similar frequencies, their loss functions and training signals were different, which could have inherently led them to learn different things.

In Outcome Supervision via RL with verifiable rewards, as implemented in DeepSeek-R1 [14], the model optimizes the sparse final-answer reward over a long trajectory. This gives the model freedom to explore during that trajectory by trying various reasoning paths, backtracking, and refining its responses autonomously. When a gradient update is issued, it reflects information from that entire sequence of actions, which allows the model to learn from its full exploration history.

In contrast, Process Supervision via SFT prescribes a fixed trajectory. It forces the model using cross-entropy loss to conform to one target sequence, which is treated as the "gold standard". Each gradient update penalizes deviations from the training distribution, regardless of whether creative reasoning paths could lead to correct answers. As a result, SFT discourages exploration and enforces imitation, potentially limiting the model's robustness.

Thus, despite the same token exposure and optimizer update frequency, Zeng-OS may have benefitted from substantially richer learning signals for each update. This likely contributed to its superior baseline performance relative to Cheong-PS and helps explain why Cheong-PS exhibited issues such as failing to emit the EOS token and looping its outputs.

5.1.2. Main Finding's Relation to Prior Work

At first glance, one might conclude that because Zeng-OS demonstrated greater robustness than Cheong-PS, the results invalidate prior literature asserting that Process Supervision yields more coherent reasoning. However, this interpretation is not correct.

As discussed in Section 2.2, prior studies comparing Outcome and Process Supervision [5], [17] generally did not very strictly control for training effort and other confounding factors. While this may have made the comparison slightly less fair, it did not make their insights any less useful. They showed the important result that if each supervision strategy was allowed to proceed with the compute and time it needs, then Process Supervision (especially a PRM, which this study did not investigate) could be more reliable.

This work offers a new perspective. It shows that when we do attempt to control for these confounders by aligning training exposure and gradient update frequency, Outcome Supervision via RL with verifiable rewards would lead to lower rates of "CoT bypass" errors than Process Supervision via SFT. It does not make a general statement about the desirability of Outcome or Process Supervision as a whole, as there are other strategies within these classes (like ORMs and PRMs) that were not studied in this paper.

More importantly, this work highlights salient limitations in the methodology employed to align training effort. The two variables that were fixed may not have fully captured the underlying differences in "amount of information learned" between models. Future work will need more precise methods for quantifying this property to enable even fairer comparisons between Outcome- and Process-Supervised models.

5.2. 16-shot CoT prompt affects task accuracy but does not fix underlying SCMs

Zeng et al. [18] explicitly omitted the format reward when creating Zeng-OS, citing that it hindered exploration. Consequently, when Zeng-OS was required to conform to a fixed format prescribed by the 16 examples, it may have struggled to adapt, explaining its decline in task accuracy. This indicates that in training an LRM with RL, there might be a tradeoff between exploration and instruction-following as the model would want to solve problems in its way.

In contrast, Cheong-PS benefitted from the 16-shot prompt, particularly on previously weaker tasks, likely because SFT explicitly trains the model to imitate provided examples. This exposure to imitation made Cheong-PS more receptive to few-shot demonstrations.

Nevertheless, the underlying SCM classifications could have remained largely invariant as the reasoning behavior is a fundamental property shaped primarily by training (the deepest level of influence), whereas variations in the prompt are too shallow to correct such structural deficiencies.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

The preceding sections have comprehensively outlined the limitations of the current method for matching the training effort between Cheong-PS and Zeng-OS. Additional limitations include the fact that only one model of a single size class (Qwen-2.5-7B) was studied, and that this model already exhibited strong baseline mathematical abilities. Furthermore, a significant portion of the gold CoTs used for Cheong-PS were sampled from Yeo et al. [20], who used a Qwen-2.5-Math-72B-Instruct model to generate these traces. As a result, the quality of the CoTs may not have been fully optimal, potentially contributing to Cheong-PS's reduced performance.

As discussed in Section 5.1.2, future work should aim to develop improved methods for matching the training effort of models trained under fundamentally different supervision strategies. Better metrics are needed to quantify the "amount of information a model has learned" beyond token exposure or optimizer update frequency. Another next step would be to replicate this study while replacing Process Supervision via SFT with Process Supervision via RL using a PRM as the LLM judge. This way, both Zeng-OS and Cheong-PS would be RL-trained, thus the task of matching their training effort could be more tractable.

6. Conclusion

LRMs hold significant promise, but to fully unlock their potential, the failure modes associated with different training techniques must be characterized under rigorously controlled conditions. This study compared two LRMs, one trained with Outcome Supervision via RL with verifiable rewards, and the other with Process Supervision via SFT, while matching token exposure and optimizer update frequency. Using SCM analysis to detect "CoT bypass" errors, it observed that the Outcome-Supervised model exhibited greater reasoning robustness under these conditions. These results contribute an early datapoint that characterizes one type of logical error across training strategies. They highlight the limitations of the employed method for matching training effort and underscore the need for more rigorous evaluation strategies in future work.

Appendix A

Training hyperparameters for Cheong-PS are detailed in this section.

Zeng et. al (2025) were contacted via a GitHub Issue to clarify the training effort required to create Zeng-OS. It was confirmed that 90 rollouts went into Zeng-OS's training. Since the number of times the model saw the prompt was 96 for a 100 rollouts, then the corresponding number for 90 rollouts was computed as .

Secondly, training of Cheong-PS was done on a 4x NVIDIA L40S node using the Axolotl SFT framework and DeepSpeed ZeRO-3. The longest sequence in the dataset prepared to train Cheong-PS had 4352 tokens, and thus 4352 was selected as the maximum context length. Then, Axolotl's sample packing feature was enabled. This managed to fit ~6.7 full examples of prompt+CoT+answer in every sequence of length 4352. The figure of 6.7 was obtained from the following calculation:

- The dataset size was .

- Without sample packing, iterating over the full dataset with a batch size of 256 yielded steps.

- Once sample packing was enabled, this number decreased to 428.

- This indicates that full text sequences were crammed into each window of length 4352.

Therefore, to ensure that 1 optimizer update was issued every ~256 math questions (counted with multiplicity), the per GPU batch size was 1, and there were 10 gradient accumulation steps. This created an effective batch size of (1 batch per GPU) (4 GPUs) (10 accum steps) . And, within 40 complete sequences, roughly math questions were packed.